A poet’s poet.

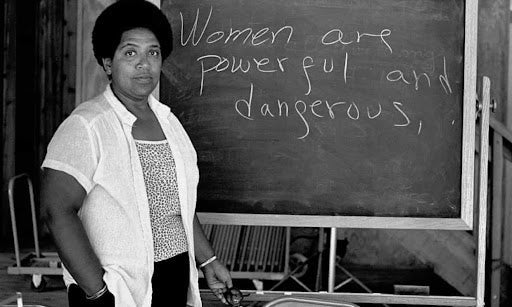

“If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” – Audre Lorde

Audre Geraldine Lorde was born February 18, 1934 and was the youngest of three girls to Grenadian immigrants, Poets.org reports. She attended Catholic school as a child and took an interest in writing at an early age; she was still in high school when she had her first poem published in Seventeen magazine, The Poetry Foundation reports.

“I used to speak in poetry. I would read poems, and I would memorize them. People would say, ‘Well what do you think, Audre? What happened to you yesterday?’ And I would recite a poem, and somewhere in that poem would be a line or a feeling I would be sharing. In other words, I literally communicated through poetry. And when I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry, and that was when I was twelve or thirteen,” Lorde once told reporters.

She went on to earn her bachelor’s degree from Hunter College and a master’s from Columbia University, working as a librarian in New York public schools during the 60s. Lorde married Edward Rollins in 1962, the couple having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathon, before divorcing in 1970. Just two years prior, Lorde published her first collection of poems, The First Cities (1968).

Lorde became a strong voice for those living in the margins, regularly exploring the intersections of racism, sexism, classism and homophobia. After her career as a librarian, Lorde became a writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi where she met her life partner, Frances Clayton. She would go on to release several other critically acclaimed works, including Cables to Rage (1970), New York Head Shot and Museum (1974), and Our Dead Behind Us (1986).

It was her work as a professor and her existence as a Black, queer writer in white academia that informed majority of her work. Lorde passed away in 1992 from cancer. In the years since, her work has continued to inform many of our liberation politics and become a guiding light for freedom. In today’s culture, we have a habit of making artists and their work disposable, something we are actively against here at Because of Them We Can. To make sure you never forget the contributions of those who paved the way, here are 5 good reasons why we should talk about Audre Lorde more often:

She spoke truth to power.

Her work was a major contribution to feminist theory and critical race studies, Lorde using her own personal experiences in service of the political agenda.

“I have a duty to speak the truth as I see it and to share not just my triumphs, not just the things that felt good, but the pain, the intense, often unmitigating pain,” she once said.

Lorde was a champion for liberation movements and LGBTQ+ rights.

She spoke out against the marginalization of categories like “Black woman,” and “lesbian,” choosing instead to center liberation and humanity in all of her work. Lorde was a part of the second-wave feminism movement, civil rights, Black cultural, and LGBTQ+ movements.

“My sexuality is part and parcel of who I am, and my poetry comes from the intersection of me and my worlds… objection to my work is not about obscenity … or even about sex. It is about revolution and change.”

She was not afraid to document her most vulnerable moments in service of the greater good.

In 1980, Lorde published a recount of her journey to overcome breast cancer in The Cancer Journals, widely regarded as one of the most impactful illness narratives to date. Lorde confronts her own mortality and deep dives into her lived experiences.

“Prosthesis offers the empty comfort of ‘nobody will know the difference.’ But it is that very difference which I wish to affirm, because I have lived it, and survived it, and wish to share that strength with other women. If we are to translate the silence surrounding breast cancer into language and action against this scourge then the first step is that women with mastectomies must become visible to each other.”

Lorde was an advocate for Black women globally.

In 1981, Lorde and writers Cherríe Moraga and Barbara Smith founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, a publication committed to amplifying the work of Black feminists. Lorde also lent her voice to the struggle of Black women in South Africa under apartheid regime, creating Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa.

She is an internationally recognized artist and activist.

She was a fellow of the National Endowment for the Arts, a longtime professor of English at John Jay College and Hunter College, and poet laureate of New York from 1991 until her death in 1992. Lorde has nearly 20 published works and today, the Audre Lorde Project continues her work with a number of programs focused on community organizing and justice.

“Her imagination is charged by a sharp sense of racial injustice and cruelty, of sexual prejudice…She cries out against it as the voice of indignant humanity. Audre Lorde is the voice of the eloquent outsider who speaks in a language that can reach and touch people everywhere,” said former New York Governor Mario Cuomo.

Thank you for everything Audre!

5 good reasons why we should be talking more about Audre Lorde. Photo Courtesy of Robert Alexander/Getty Images

Wonderful article. Thank you for connecting me to the Audre Lorde Project. I look forward to continuing to learn about Ms Lorde and the gift that she is to this world. 🙏🏾